Michael Sherwin is an Associate Professor of Photography and Intermedia in the School of Art and Design at West Virginia University. Using the mediums of photography, video and installation, his work reflects on the experience of observing nature through the lenses of science and popular culture. He has won numerous grants and awards for his work, and has exhibited widely, including recent shows at the Huntington Museum of Art in Huntington, WV, Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences in Charleston, WV, CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, NY, SPACES Gallery in Cleveland, OH, PUNCH Gallery in Seattle, WA and the Center for Emerging Visual Artists in Philadelphia, PA. Sherwin earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Oregon in 2004, and a Bachelor of Fine Arts from The Ohio State University in 1999. He has been a member of the faculty at the University of Oregon and Central Washington University. He is also an active and participating member of the Society for Photographic Education and the lead instructor for WVU's Jackson Hole Photography Workshop.

(Editor's note: this is the first Looking at Appalachia post with our overhauled theme, which offers larger photographs. Enjoy the new design and please feel free to share any feedback.)

Roger May: Your current body of work, Vanishing Points, is moving into its fifth year. How have you seen the project evolve since you started?

Michael Sherwin: Initially, I was pretty clinical in my approach. I was making photographs with a very wide angle, attempting to encompass as much of the landscape as possible. I was mostly shooting in places that were designated archaeological sites, and careful to include some evidence of the history in the photograph. As the project progressed into Ohio I felt my approach loosening. I was following the newly established Ancient Ohio Trail, which connects numerous sites via a driving route. Rather than just focusing on the actual sites, I began to acknowledge the journey more and more. I started making photographs that were literally along the road, or of subjects that caught my eye while traveling from one point on the map to another. Many of these newer images are of isolated subjects, or details of a much larger landscape, such as an old stump with shoots growing out of it, a deer blind or prayer hands. I like to think of these as symbols, or metaphors, for the larger conversation. I also like the way these newer images add a fresh narrative element to the series. In turn, the sequencing of images has become really important to me.

RM: I’m particularly drawn to the absence of people in this series. Certainly there are human elements from both past and present generations, but can you tell me about this decision as an element of the series?

MS: I actually made several portraits early on in the project, but nothing I felt strongly about, and not enough of them really to include. Although there are no direct portraits in the series, there are people included at a distance in several of the images, some fishing, some praying and some exploring. You can’t really identify with any of these people; they are merely a part of the larger landscape in which they exist. This was not a deliberate decision. I have always been more comfortable working with landscape as a subject matter and I guess that’s where I focused my energy.

RM: I appreciate how quiet this work is on the surface, but how transformational each individual image becomes when you consider the full weight of Manifest Destiny on Native American population and culture. It struck me that there are many parallels with Manifest Destiny and the extractive industries (mountaintop removal coal mining) in Appalachia, specifically West Virginia. In the name of modernization and American prosperity, people of the region - old and new - suffer the effects of outside industry and influence. Can you talk a little about this?

MS: Progress, in the name of big industry and personal gain, is trumping careful consideration of the historical and cultural significance of the landscape and people of West Virginia and throughout the country. Much like the onset of Manifest Destiny in the 19th century, outside interests in the mineral resources of West Virginia have little to no concern about the quality of life of the people who call it home. I’ve lived all over the country, including nine years in the Northwest, and I’ve never seen a landscape so ravaged and mishandled as West Virginia. This struck me upon moving here in 2007 and even more so as I ventured out to photograph throughout the state. Because of its economic reliance on extractive industries, the state has opened itself up to the worst kind of environmental degradation – mountaintop removal coal mining. Not only does this type of mining have horrendous and irreversible effects on the land, it’s also dispossessing thousands of rural families and destroying communities.

Whether driven by divine right, or money, the products of Manifest Destiny continue to way heavy on our landscape and indigenous cultures. I’ve witnessed this right here in Morgantown, WV, where the population is growing rapidly and unchecked building seems to be happening everywhere in the name of progress. The monstrous Suncrest Towne Center, which inspired the project and was built less than a mile from my house, exists on an ancient Monongahela burial and village site. As an American with Irish-German ancestry I realize I am a product of Manifest Destiny. In a way this series is an attempt to grapple with this legacy and to connect to a previous cultural understanding of the land and spirituality that I more closely identify with.

RM: How important is writing about your work in the editorial process? Can you talk a little about your working process, how you identify locations to make pictures, and how you stay motivated to make this deeply engaging work?

MS: I have kept a journal from the very beginning of this project. The contents include notes about possible locations, itineraries, clippings, contact info, inspirational quotes and musings, and a rambling narrative about my outings. The journal helps me keep all the pieces of the puzzle together, albeit in a somewhat disorganized manner. I often review it to remember a name of a person or place visited or to reread a certain passage. At some point, it might be fun to see the text, or journal, exist in the same space as the images.

It’s a difficult process to identify locations. I do a lot of research online, read books and meet with people to discuss my project. Some of the sites I visit exist in state parks or monuments, which are easy to locate, but many others are intentionally kept from the public. I use Google Earth a lot and make a map of sites to visit with detailed directions before ever leaving the house. Of course, things come up along the journey in talking with people who actually know the landscape. The locals are often the best resource for locations and sites not found on any map. I’ve found that I really enjoy this process of discovery. Much like hiking through a new landscape, or paddling a meandering river, I’m always wondering what’s around the next corner. The project continues to unfold as I progress, encouraging me to keep exploring and sharing my discoveries.

RM: This series deals with many elements, but there is this theme of time that I find intriguing. Reaching back into history can often lead us into uncomfortable territory, yet the beauty of each individual picture seems to lighten those blows. Time is also required to study the pictures, to connect the story of the past to the constructed image we’re looking at when we look at the expanse of the Suncrest Town Center in Morgantown, West Virginia. How do you communicate the importance of time, especially the breadth of time the project addresses?

MS: There’s an unwritten history embedded in the landscape of Appalachia. Layers and strata of time are occasionally unearthed and a story unfolds. I’m really interested in how the land holds secrets and vessels of time unknown. When I visit an ancient site, or designated sacred site, I am very sensitive to this deep sense of time and history. However, nearly everywhere you look evidence of our modern civilization intrudes. There’s a fascinating push and pull between the mysterious past and familiar present at these sites. I feel this duality when I’m working in the field and attempt to translate it in the photographs.

Some of the photographs in the series are more direct and ironic, while others combine the atmosphere of light and time to create a more ephemeral scene. In certain images, the land, with all its mystery and beauty, seems to hold a quiet power in the presence of trivial human artifacts. As permanent as things may appear, our own civilization is subject to the slow grate of time and change. At some point in the distant future our own culture will be defined by the remains we left behind.

RM: As an educator, how do you convey the importance of long-term work to your students? We are inundated with visual imagery these days, yet we aren’t necessarily more visually literate as a culture. How has your experience with long-term projects informed your teaching style and appreciation for similar work?

MS: It’s been really fun and challenging to throw myself into the Vanishing Points project and allow it to evolve over the past several years. This is the first serious long-term project I’ve undertaken and it’s quite different from my previous work, which involved a lot of video, appropriation and experimental installations. At times, it has been difficult for me to accept a project that is so traditional and straightforward in terms of technique. At the same time, however, I’ve rekindled my appreciation for straight photography and discovered a whole bunch of other artists, both current and past, that have similar styles. Many of these artists have spent multiple years, even a decade or more, on a single project, which has been reassuring.

Unfortunately, my students are not given the kind of time I have to focus on a single project. In fact, it’s hard for them to focus on a project for more than one semester. However, when they get to their final semester, I often see a lineage in their content that goes back to their first photographs/projects three years prior. We talk about these early images and ideas and how they relate to what they’re currently working on. In their final semester they are required to create a presentation, which draws on their resources and influences and connects their work and ideas. I remind them that their work will often take on many different appearances throughout their career, but they will eventually see overarching concepts and personal motivations coalesce.

All photographs © Michael Sherwin. All rights reserved.

- Big Bottom Massacre State Memorial, Morgan County, Ohio.

- Conus Mound, Mount Cemetery, Marietta, Ohio.

- Grave Creek Mound, Moundsville, West Virginia.

- Laundry, Indian Mound Campground, New Marshfield, Ohio.

- Air Force Museum, Dayton, Ohio.

- Shrum Mound, Columbus, Ohio.

- Suncrest Towne Center, Morgantown, West Virginia.

- Boat Ramp, Greenbottom Wildlife Management Area, West Virginia.

- Factory, Ohio River, Marshall County, West Virginia.

- Chickamunga Mound, Chattanooga, Tennessee.

- Sunrise, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Chillicothee, Ohio.

- Dead Fox, James A. Rhodes Appalachian Highway, Vinton County, Ohio.

- View from the Top, Criel Mound, South Charleston, West Virginia.

- Fishing, Muskingum River, Lowell, Ohio.

- Mattress, Natrium Plant, New Martinsville, Ohio.

- Miamisburg Mound, Miamisburg, Ohio.

- Mural, Point Pleasant Riverfront Park, Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

- Prayer Hands, Faith Chapel, Vinton County, Ohio.

- Rail Lines, Moundsville, West Virginia.

- Stump, Great Miami River, Hamilton, Ohio.

- Shawnee Overlook, North Bend, Ohio.

- Soybean Field, Buffalo, West Virginia.

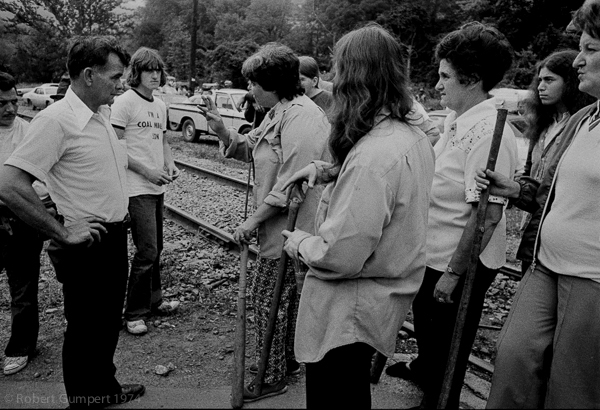

SEEN AND FELT: Appalachia, 2012

SEEN AND FELT: Appalachia, 2012